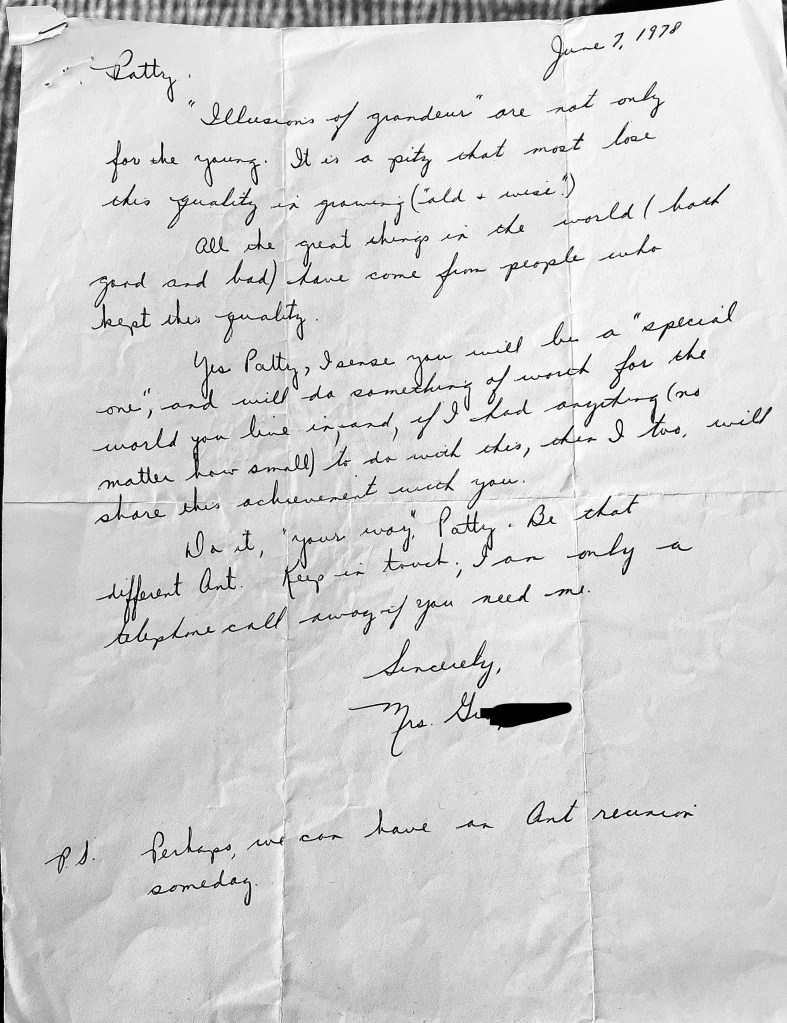

Over the weekend I discovered a note given to me by my Social Studies teacher when I was 14 (1978). I clearly remember the circumstances surrounding it: my father or my stepmother had told me that I had ‘illusions of grandeur’. I went to this teacher, Mrs G, upset. Ever since I could remember, I had harboured feelings of wanting to do something important, something meaningful. I don’t know why I apparently confided in my father or stepmother — but I do remember being very hurt by them. I felt belittled.

Mrs G however: as the note above shows, she believed in me. For my part, I adored her, absolutely adored her (as I did many teachers throughout my formal education, feeling handed between them like a baton in a relay race, for safe keeping). She was mischievous, an individualist, and taught me more about good essay writing than anyone else, before or since.

I must have kept this folded piece of paper because it helped. She believed that I could do something. And she would know. She would know, I thought, possibly more than my father or stepmother would. She was in the world in ways they weren’t — I sensed this, already.

Now though what strikes me about this note are the words at the end: ‘I am only a telephone call away if you need me.’

I have no memory of these words. No memory of that level of care at this age — the age at which I now know some of the most harrowing and damaging instances of sexual abuse occurred, seemingly relentlessly. I wonder what I thought about those words then? Would I have considered speaking with her? Would I have ever thought about phoning?

And why such a pointed offer of help? Did I show more than I think I did? Did she suspect anything?

I was a very high achiever throughout my formal education. I was not shy. I had friends. I was principled, political, and often revelled in being ‘a bit different’, particularly in terms of fashion. By age 15, in the days of mostly preppie wear, I wore patent leather heels, balloon black trousers, a thrifted double breasted red top, and put my hair in tiny braids so that it was all kinky the next day. Etc. Yet: I never misbehaved. I never actively rebelled.

I now know that I stuffed the sexual abuse I was experiencing into a box in my head — and slammed the lid down tight. I did this almost from the start, almost knowingly. I remember the gut response when my mind flitted to the abuse: pay attention to what you like: forget everything else, forget it. This separation of mind and body preserved my mental health for many years. Until it didn’t. I know this story is so familiar to so many.

Recently there’s been a bit of discussion on X (Twitter) about whether signs of abuse were missed in us survivors when we were being abused. And the more I think about it, the more I become confused. Maybe there was enough ‘unusual’ about me to make teachers think, or wonder? Certainly I was always hailed as ‘very mature’ for my age — not physically, but emotionally. I often felt out of step with peers. All the talk of boyfriends, crushes, and dates — I found excruciating and terrifying in equal measure. I wanted nothing to do with it. My overriding priorities were learning, writing, and ballet. Not much else mattered very often. This might have been interpreted as ‘mature’? Was it noticeable? Was this a ‘sign’?

The truth is, I never would have phoned Mrs G, although from here I fervently wish I had been able to. And there were other teachers, after her, who often seemed to be waiting for me to say something. But what? What?

What can children say about the dangers they live in? Precious little, I think, is the answer even now. So it’s up to teachers? But that can’t be right either, as even if something (what?) is ‘noticed’ — chances are high that a child will lie when asked directly. I am certain I would have.

There are so many variations of ‘signs’ of abuse — many that are in fact seen as ‘fine’ (good behaviour, quiet etc) — that there is no rulebook here. None of us can produce a definitive list. What’s clear however is that adults in the position to notice need to be given the training and the space to act; similarly, children need to hear and see that sexual abuse can enter conversation. If there had been a space to speak, or to write, about what was happening to me — one that wasn’t judgemental, that didn’t put me in a vulnerable place, that wouldn’t pity me or think less of me, one that I trusted to look after me — I might, might have found a way to send a clear message.

But there was no space for that then. Despite Mrs G, and despite all of the kind adults in my school life as the years progressed — the thought of mentioning anything to them about the abuse I experienced never, ever occurred to me. And indeed: no one made me feel safe enough so that I knew, if asked, I could answer honestly. So I never even got close.

I’m heartened by the work of the many survivor-centric organisations and charities now on the ground, going into schools, speaking with medical students, within the police, with churches of almost all denominations, scouts organisations, community leaders etc. This is the training and awareness which is so desperately needed. I pray that the enormous differences they are making hold fast. I pray for a future in which a teacher, nurse, doctor, pastor, priest, vicar, scout leader — neighbour, friend, anyone — feels empowered to ask, carefully and with respect, knowing there is support available: is something happening? And for a future too where another child like me (like so many of us) might go back to Mrs G and be able to say: something is happening.

[I cannot finish this post without signposting some of these vital organisations. I really only know a bit about the UK. I urge everyone please to add more in the comments. The Flying Child Project, Survivors Voices, LOUDfence, Barnardo’s, the NSPCC, Survivors Trust.]

***

This extract from Leaving Locust Avenue follows what happened when I decided to move schools at 17, at the beginning of my senior year of high school. No one asked much, but looking back — I wonder if at least a couple of them wished for the space and permission to do so.

All I really remember about the decision to go is getting in the car and driving. I cannot remember whether I have permission. But I get in the car and drive a few roads, some out by S’s house which I love, in the country, between mountains.

I find myself at the shopping area close to our house. The strip mall, which used to have that A & P, a department store, a hairdresser. And a phone booth.

I park the car next to the phone booth. I phone, incredibly it seems now, my therapist. I have a plan. When I tell her, I sense her relief. I sense – oh as I have in so many situations, so many times over these years – a woman urging another woman to go, to run, to escape. She approves. She agrees. And I allow myself – for a millisecond of a moment only, so caught up in my own moment of course – to think that she too has been trapped by [my father].

Even now I am astonished that I know this from the conversation. But I do. And it gives me the impetus to phone my mother.

I phone her right there and then. I ask her if I can come live with her. I say I am ready. That I must, must leave. And I must leave now. She, to her credit, rises to the occasion. She asks me, once, if I am sure; I only have one more year in Blacksburg after all – am I sure? I say I am sure. And then – perhaps like my father 11 years earlier – she agrees with no hesitation, no consultation. She will have me.

I know I am going. I am 17 years old, and am a month into my senior year of high school. I am placed second in my graduating class, the salutatorian, only a whisker away from valedictorian. And I am leaving.

*

My childhood friend Val is perhaps the most upset about me going. I remember she starts crying, right in the classroom. She wants to know why. And I have my answer, the one I use over and over ‘I just want to live with my mother before going away to university.’

I do not realise that Val still cares about me. I do not realise, if I’m honest, that anyone except Alice really cares. Yet my going disturbs the surface, and numerous people – students, teachers – seek me out to wish me well, and ask questions. The Principal of the school asks me into his office to see if he can do anything to make me stay, and if everything is okay. To which I say No, and Yes.

Of course it is Mrs A [my English teacher] I dread leaving the most. But again, to her credit, she doesn’t try to convince me otherwise. She wishes me all the best. She tells I will succeed in everything I do. She believes in me.

I encounter a curious mix of sorrow and knowingness when I announce I’m leaving. Looking back, I think that the sorrow mainly comes from those who cannot imagine how this has happened. Whereas the knowingness, the unspoken, rises through the eyes of those who may know something or suspect.

From here, I see our joint powerlessness. I see how mistreatment, how abuse, is too often communicated in silence, implied. How it is up to the women to get away, how other women must urge them silently. How they are brave, deserting everything. Leaving everything – their children, their lives, their homes – behind. Forced to cut and run.

Whereas really it’s my father who needed to leave. Really he should have been arrested. And I should have been able to stay put, and never lost [my sister] and [my brother], the heartbreak of my life. And they in turn would never have had to carry their own complex and heart-breaking confusions – with no help from anyone — around for so many years.