For as long as I can remember, the holiday season has too often brought with it a pervasive melancholy. When I was little — before going to live with my father at age six — Christmas could feel uncomfortable for me: as the only grandchild for a long time, all eyes were on me, wherever I celebrated. There are numerous photos of me in front of my grandparents’ white artificial tree, this last one when I am six years old, back in Texas for Christmas, two months after moving to Virginia.

Thereafter, Christmas becomes outright fraught. With my sister and brother and stepmother and father, the dynamics intensify. I am aware of being ‘the stranger’ in the celebrations, and I remember one particular photo of my stepmother cuddling my brother and sister on the sofa to one side, while I stand in front of the tree, my tightly clasped hands behind my back reflected in the mirror behind me. Just thinking about it breaks my grown-up heart.

I have been reading The Child Safeguarding Review Panel – I wanted them all to notice over the last couple of weeks. This UK report came out in November (2024), and focuses exclusively on Child Sexual Abuse within the family. It’s a depressing read in almost every way: what is missed, who isn’t believed and why, the devastating lack of resources for abused children and families, the over-reliance on ‘evidence’ and on the children themselves disclosing. However, a couple of aspects have struck me with force: first, that so often neglect is a hallmark of an abusive environment. If a child is not neglected, if a child is being cared for, watched out for — sexual abuse is much less likely to occur.

I was emotionally neglected throughout much of my childhood, and when I was living with my mother, physically neglected as well. Despite growing up in a firmly middle-class household, it’s clear that some basic needs weren’t met. This in turn contributed to making me vulnerable; I welcomed any attention I could get from my family, specifically my father. I now see that he groomed me by showing me attention, and then manipulated this into sexual abuse.

Pretence is another common denominator in abusive households. In my life, these layers of everything having to appear ‘fine’ and ‘happy’ seemed to triple at Christmas. We often went to family in Alabama, Florida, or Texas for a week over the holidays. The strain of having to appear ‘just fine’ cast a long shadow every year. The sheer irony of opening presents, having to ‘be a child’ amongst other children haunted me from the moment my father started abusing me. I wasn’t like other children — and I knew it. My childhood was irretrievable. I knew this too.

At Christmas, I often felt trapped. The family was forced into close proximity. I had no friends nearby, nowhere to go, nothing (except reading) to distract me. And I absolutely dreaded nighttimes. I was utterly terrified that my father would come into the room I was inevitably sharing with my siblings or with cousins — he’d done so before — and that then they would ‘find out’ what was happening.

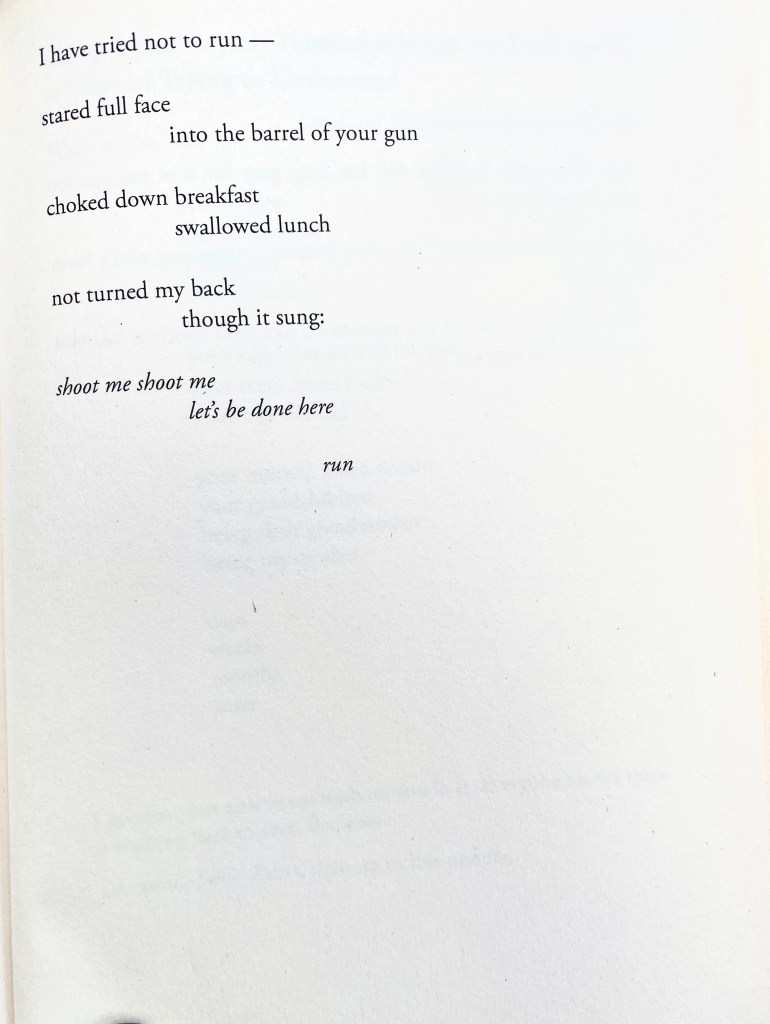

The awful thing here is: I really felt it was my responsibility to keep up family appearances. It was my job to be careful, to make sure no one found out, because otherwise…..otherwise what? All these decades later the only answer I have is that if anyone found out they would simply hate me. Hate me for ruining their lives. Blame me for everything going ‘wrong’.

I am lucky now to have my own healthy family, my separate family traditions — which I created alongside my husband and children and extended family. I am lucky that I no longer feel in danger, or have to pretend for days at a time. I cannot and will not pretend about anything anymore.

So. Please remember that at this time of year there are children for whom Christmas is an ordeal. There are children who have to work extra hard to maintain the pretence, or who are afraid in their beds at night — doubly so, because there is nowhere else to go. Some children — like me — are happier at school, or at friends’ houses. For some children being with family is the last place they would choose to be.

Please remember too that as upsetting as it is to grasp: all of us — you, and you, and you — will know people who are perpetrating sexual abuse. At least 10% of the population is sexually abused before the age of 16. The vast majority of this abuse is perpetrated by family men. They do not appear to be ‘monsters’. They do not appear to be ‘sick’ or ‘unusual’. They make sure that they cultivate looking like a ‘normal’ family. Yet they commit abhorrent crimes. These are the facts.

Due to Gisele Pelicot’s courage, over 50 families (who no doubt consider themselves ‘normal’) must come face to face this Christmas with what lies beneath the surface of their ‘ordinary’ lives. It’s the tip of a huge iceberg, the excavation of which is long overdue. These families are not the exceptions — they are in fact now experiencing what is for large portions of society the hidden norm. Although the road ahead is long and distressing, I join with so many in hoping that this uncovering now has some momentum. Children — and victim survivor women and men — deserve a life free from shame and blame. Shame Must Change Sides.