But we can do this.

More soon.

Hold tight.

But we can do this.

More soon.

Hold tight.

I have been feeling silenced.

It’s taken me 10 weeks to come here and say this. That’s how silenced I have felt.

What silences sexual abuse victim/survivors? What silences ME?

To somewhat answer this, I’d like to highlight this article. Absolutely none of it will be news to survivors who struggle with their families, particularly if the sexual abuse they suffered was perpetrated by a member of the family.

None of this is news, but none of this can be solved either.

I cannot say much more. I have written and erased this post several times. This is how silenced I feel, and how much I am checking myself, worrying about my words.

For weeks my husband, children, other family, and close friends have been my scaffolding. Alongside me and checking in every day. Thanks to them, and to the years of excellent therapy, the ‘top up’ therapy I’m doing now — I know I’m okay, and always will be.

I love my life. I won’t be dragged back into tangles of secrets and blame. There’s no reconciliation in that. In the words of glorious Fleetwood Mac: never going back again.

This is one of the recurring dreams I had during the abuse, and afterward during my initial therapy. I have felt very much like this over the last few weeks. Nothing to stand on, falling, exposed.

But I’m back on my feet now. For good.

from my memoir, Leaving Locust Avenue:

***

I have versions of the same dream.

This time I am freezing. I am freezing because I hardly have anything on, and the wind blowing through the walls, the walls that aren’t there, is cold. Still I have to decorate, I have to stand on the chair and hang plants, think about colours, make things just so. I begin to shiver, and the leaves of the plant I am holding shake with my shivering. I try to stop, but the more I try to stop the worse it becomes, until my whole body is shaking.

I manage to hang the plant, putting the chain over the hook. I manage to smile into the darkness, push my hair back as if in front of a mirror. Then I take a step off the chair, and my foot keeps going down, down further than I thought the floor was, and when it touches, I fall after it into a ditch.

I know I have broken some bones, because they are too cold and brittle. My arms are pinned to my side in the ditch, my face pushed into the mud. In the fall I lose my nightgown, and my bottom is exposed. But I can’t move. I am useless, and leave myself there for dead.

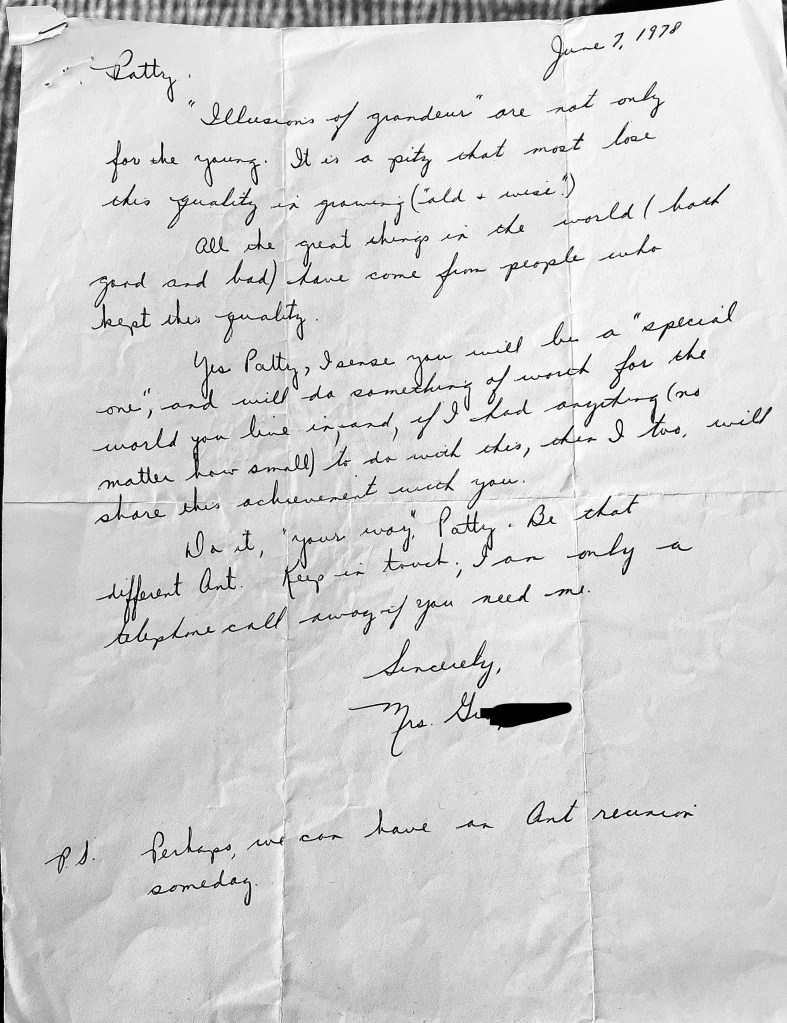

Over the weekend I discovered a note given to me by my Social Studies teacher when I was 14 (1978). I clearly remember the circumstances surrounding it: my father or my stepmother had told me that I had ‘illusions of grandeur’. I went to this teacher, Mrs G, upset. Ever since I could remember, I had harboured feelings of wanting to do something important, something meaningful. I don’t know why I apparently confided in my father or stepmother — but I do remember being very hurt by them. I felt belittled.

Mrs G however: as the note above shows, she believed in me. For my part, I adored her, absolutely adored her (as I did many teachers throughout my formal education, feeling handed between them like a baton in a relay race, for safe keeping). She was mischievous, an individualist, and taught me more about good essay writing than anyone else, before or since.

I must have kept this folded piece of paper because it helped. She believed that I could do something. And she would know. She would know, I thought, possibly more than my father or stepmother would. She was in the world in ways they weren’t — I sensed this, already.

Now though what strikes me about this note are the words at the end: ‘I am only a telephone call away if you need me.’

I have no memory of these words. No memory of that level of care at this age — the age at which I now know some of the most harrowing and damaging instances of sexual abuse occurred, seemingly relentlessly. I wonder what I thought about those words then? Would I have considered speaking with her? Would I have ever thought about phoning?

And why such a pointed offer of help? Did I show more than I think I did? Did she suspect anything?

I was a very high achiever throughout my formal education. I was not shy. I had friends. I was principled, political, and often revelled in being ‘a bit different’, particularly in terms of fashion. By age 15, in the days of mostly preppie wear, I wore patent leather heels, balloon black trousers, a thrifted double breasted red top, and put my hair in tiny braids so that it was all kinky the next day. Etc. Yet: I never misbehaved. I never actively rebelled.

I now know that I stuffed the sexual abuse I was experiencing into a box in my head — and slammed the lid down tight. I did this almost from the start, almost knowingly. I remember the gut response when my mind flitted to the abuse: pay attention to what you like: forget everything else, forget it. This separation of mind and body preserved my mental health for many years. Until it didn’t. I know this story is so familiar to so many.

Recently there’s been a bit of discussion on X (Twitter) about whether signs of abuse were missed in us survivors when we were being abused. And the more I think about it, the more I become confused. Maybe there was enough ‘unusual’ about me to make teachers think, or wonder? Certainly I was always hailed as ‘very mature’ for my age — not physically, but emotionally. I often felt out of step with peers. All the talk of boyfriends, crushes, and dates — I found excruciating and terrifying in equal measure. I wanted nothing to do with it. My overriding priorities were learning, writing, and ballet. Not much else mattered very often. This might have been interpreted as ‘mature’? Was it noticeable? Was this a ‘sign’?

The truth is, I never would have phoned Mrs G, although from here I fervently wish I had been able to. And there were other teachers, after her, who often seemed to be waiting for me to say something. But what? What?

What can children say about the dangers they live in? Precious little, I think, is the answer even now. So it’s up to teachers? But that can’t be right either, as even if something (what?) is ‘noticed’ — chances are high that a child will lie when asked directly. I am certain I would have.

There are so many variations of ‘signs’ of abuse — many that are in fact seen as ‘fine’ (good behaviour, quiet etc) — that there is no rulebook here. None of us can produce a definitive list. What’s clear however is that adults in the position to notice need to be given the training and the space to act; similarly, children need to hear and see that sexual abuse can enter conversation. If there had been a space to speak, or to write, about what was happening to me — one that wasn’t judgemental, that didn’t put me in a vulnerable place, that wouldn’t pity me or think less of me, one that I trusted to look after me — I might, might have found a way to send a clear message.

But there was no space for that then. Despite Mrs G, and despite all of the kind adults in my school life as the years progressed — the thought of mentioning anything to them about the abuse I experienced never, ever occurred to me. And indeed: no one made me feel safe enough so that I knew, if asked, I could answer honestly. So I never even got close.

I’m heartened by the work of the many survivor-centric organisations and charities now on the ground, going into schools, speaking with medical students, within the police, with churches of almost all denominations, scouts organisations, community leaders etc. This is the training and awareness which is so desperately needed. I pray that the enormous differences they are making hold fast. I pray for a future in which a teacher, nurse, doctor, pastor, priest, vicar, scout leader — neighbour, friend, anyone — feels empowered to ask, carefully and with respect, knowing there is support available: is something happening? And for a future too where another child like me (like so many of us) might go back to Mrs G and be able to say: something is happening.

[I cannot finish this post without signposting some of these vital organisations. I really only know a bit about the UK. I urge everyone please to add more in the comments. The Flying Child Project, Survivors Voices, LOUDfence, Barnardo’s, the NSPCC, Survivors Trust.]

***

This extract from Leaving Locust Avenue follows what happened when I decided to move schools at 17, at the beginning of my senior year of high school. No one asked much, but looking back — I wonder if at least a couple of them wished for the space and permission to do so.

All I really remember about the decision to go is getting in the car and driving. I cannot remember whether I have permission. But I get in the car and drive a few roads, some out by S’s house which I love, in the country, between mountains.

I find myself at the shopping area close to our house. The strip mall, which used to have that A & P, a department store, a hairdresser. And a phone booth.

I park the car next to the phone booth. I phone, incredibly it seems now, my therapist. I have a plan. When I tell her, I sense her relief. I sense – oh as I have in so many situations, so many times over these years – a woman urging another woman to go, to run, to escape. She approves. She agrees. And I allow myself – for a millisecond of a moment only, so caught up in my own moment of course – to think that she too has been trapped by [my father].

Even now I am astonished that I know this from the conversation. But I do. And it gives me the impetus to phone my mother.

I phone her right there and then. I ask her if I can come live with her. I say I am ready. That I must, must leave. And I must leave now. She, to her credit, rises to the occasion. She asks me, once, if I am sure; I only have one more year in Blacksburg after all – am I sure? I say I am sure. And then – perhaps like my father 11 years earlier – she agrees with no hesitation, no consultation. She will have me.

I know I am going. I am 17 years old, and am a month into my senior year of high school. I am placed second in my graduating class, the salutatorian, only a whisker away from valedictorian. And I am leaving.

*

My childhood friend Val is perhaps the most upset about me going. I remember she starts crying, right in the classroom. She wants to know why. And I have my answer, the one I use over and over ‘I just want to live with my mother before going away to university.’

I do not realise that Val still cares about me. I do not realise, if I’m honest, that anyone except Alice really cares. Yet my going disturbs the surface, and numerous people – students, teachers – seek me out to wish me well, and ask questions. The Principal of the school asks me into his office to see if he can do anything to make me stay, and if everything is okay. To which I say No, and Yes.

Of course it is Mrs A [my English teacher] I dread leaving the most. But again, to her credit, she doesn’t try to convince me otherwise. She wishes me all the best. She tells I will succeed in everything I do. She believes in me.

I encounter a curious mix of sorrow and knowingness when I announce I’m leaving. Looking back, I think that the sorrow mainly comes from those who cannot imagine how this has happened. Whereas the knowingness, the unspoken, rises through the eyes of those who may know something or suspect.

From here, I see our joint powerlessness. I see how mistreatment, how abuse, is too often communicated in silence, implied. How it is up to the women to get away, how other women must urge them silently. How they are brave, deserting everything. Leaving everything – their children, their lives, their homes – behind. Forced to cut and run.

Whereas really it’s my father who needed to leave. Really he should have been arrested. And I should have been able to stay put, and never lost [my sister] and [my brother], the heartbreak of my life. And they in turn would never have had to carry their own complex and heart-breaking confusions – with no help from anyone — around for so many years.

I thought I would take a minute here to acknowledge the shifting of my memoir title from Learning to Survive to Leaving Locust Avenue. First things first: a big THANK YOU to Caroline Litman, gifted writer and fellow Highly Commended author in the Bridport Memoir Awards. She read my book, and floated this title with me. I immediately knew it was right. So grateful to her for this stroke of insight.

Second: the title makes clear that this house is at the centre of the abuse. On this avenue. In Southwestern Virginia suburbia. It feels right and important to flag here that Child Sexual Abuse occurs everywhere and anywhere. Including within the four walls of my childhood home. My sexual abuse did not happen in some ‘deprived’ area, by parents who were ‘addicts’ or ‘on benefits’ etc etc… I make these points because, believe it or not, over the last couple of years I have had people say exactly these things: ‘oh I knew it happened in some parts of town’, and ‘oh but you are doing so well, how?’ etc. All judgments of not only me now, but the circumstances I and others grew up in. And a ridiculous, shaming attitude toward those who grew up differently. This attitude conveniently keeps CSA at arm’s length — over there, not in my backyard.

Once and for all, here it is: Child Sexual Abuse happens to at least 1 in 6 children across all socioeconomic levels. I am happy to provide the resources I and others, including dozens of charities and organisations, use to arrive at this — but I would also encourage you to look it up yourself if you have questions, as along the way you will find out a great deal about Child Sexual Abuse.

My father was a professor, as were many wage earners living along this particular avenue. And his crimes were completely hidden in this house. How many more houses along this street hid Child Sexual Abuse? Statistically speaking: several. Yes, almost certainly: several.

Third and finally, I come to my leaving Locust Avenue. It was the last thing I wanted to do, in so many ways. But I felt forced out, scapegoated (as I now know is typical in family cases of abuse) — and I had to do something to save myself. As followers of this blog will know, I had to leave behind my [half] brother and [half] sister after 11 years of living with them, and was forbidden from telling them anything. It was a terrible secret to keep. Feeling forced to leave my childhood home destroyed it for me, forever, regardless of any good times there.

So yes. Leaving Locust Avenue is right. It captures so much at the heart of this book.

Here is an excerpt from the memoir which recalls when I first arrived at Locust Avenue.

***

Ommie and Granddaddy take me to Blacksburg the first time [when I am six years old]. Ever the intermediary figures, with them I feel entirely at ease. I remember no feelings of apprehension or even distress saying goodbye to my mother. I don’t remember saying anything to her, or her words to me. I believe we drive up, taking the two days along the Natchez Trace, through Alabama and a corner of Mississippi, then up through Tennessee, South Carolina and North Carolina, arriving at last in deep Southwestern Virginia, in the Blue Ridge Mountains. The only clue I have to the nature of the experience is that later my grandfather tells me he catches me sleep-walking on the journey. He wakes up in the middle of the night in the Best Western, and I am standing there, with my hand on the door handle of the room, about to open it. We are two floors up, and outside there is a metal railing around the rectangle of the pool in the middle. Needless to say, he leads me back to bed.

The house on Locust Avenue, in Blacksburg Virginia, where I mostly live for the next 11 years, is medium sized. Set in a hilly suburban area, it is a single storey olive green clapboard with a steep drive up to the carport. With three bedrooms, a living room, a lounge, dining room/kitchen and two small children, until I arrive it must seem relatively spacious. There is a large flat space out back, the only flat place in the neighbourhood in fact; in later years we brave my father’s warning of killing the grass every evening in order to play kickball, softball, and ‘ghost’. It is a real neighbourhood, with at least a dozen kids of all ages in the streets, especially in summer.

Of course, I know nothing about anything at first. I am impressed by the swings under the big tree, and remember swinging in them with a kind of aimlessness, while Ommie and Granddaddy stand close by watching.

I am impressed too by my half-brother and half-sister, six months old and two and a half, respectively. Already I have missed having siblings, and this ready-made family thrills me. I remember picking [my sister] up, and half-carrying, half-dragging her down the hallway to her room, delighted I can do it. I remember [my stepmother’s] anxiety about this action, afraid I will drop her.

[My sister] is a beautiful child, with enormous blue eyes like Granddaddy’s, and long ash blonde hair. The photograph from close to this time shows her sitting serenely with her legs tucked out to one side, in a blue velvet dress with her hands folded neatly in front of her. Her hair is pulled back just at the crown, her widow’s peak emphasising her high forehead and her gentle, serious face. In the picture she looks vulnerable, like life has caught her unawares, and it is true that from the instant I walk into that house I feel protective of her.

I am ashamed to admit that in all of our years together I never really consider the effect my entrance must have on her. It is only with my own two children, with the exact same age difference, that I can see how I – this vocal, eager to please, attention seeking child – might have overrun and quieted an already naturally introverted little girl. Suddenly [my sister] is the middle one, and despite the several visits to Texas I take in the first years, she remains so until I just as suddenly leave the house eleven years later.

Both [my sister] and I, in a sense, and differently, become stranded. It is due to her quiet determination to keep in touch that we manage to communicate at all in the years after I leave the house, given what will happen.

I imagine that for [my brother], being so young, my entrance is more seamless. My earliest memory of him is noticing his bottle propped up on the cushion of the sofa while [my stepmother] prepares dinner. I remember going over to it and holding it for him; I want someone to feed him. Is it my imagination, or does he look me in the eye then? I wonder now if my deep affection for babies begins with him, with the desire to connect.

Physically, [my brother] too has the long face, the blue eyes of our family. He is always [my stepmother’s] baby though, and I have clear memories of him sitting on her lap, her going through his hair, looking in his ears, grooming him like a chimp grooms her little one. For many years, until recently, he and I fall entirely out of contact, which I regret. As with so much else, I feel I failed him. It was not my job to catch him when so many things seemed to fall apart, first for me, then for him; nevertheless, I wish I had been able to.

And what of my father and stepmother? They inspire in me no emotions, and I suppose at first I look at them as just the next set of grown-ups to take care of me. I am used to living elsewhere, so at first my father’s house is just another in a long line. I remember that he has black glasses and dark hair. I remember [my stepmother’s] long hair and long legs, her quiet, slow-moving ways. Her distance. My father teaches mathematical physics at Virginia Tech, and is at work most of the time. I remember a few arguments, raised voices, and going into school afraid that they will get divorced. But in the main, I remember no display of emotions either from my side or theirs, only the unspoken sense that I have to be good – I have to behave – in order to stay. And that staying is imperative. Underneath it all, beneath the daily smooth running of life, things are desperate somewhere, and I know it. And as is the way with children, I end up feeling like everything, all the ways in which this will or won’t work — everything ultimately depends on me.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my mother over the last few weeks. Her illnesses. Her pathology. Her recurring cries for help.

She unfortunately married an abuser. Who, over ten years after they were divorced, began to abuse me. When I think back to telling her I was abused…I wonder if then, right then, she gave up almost completely.

My aunt and I believe that my grandmother was also abused by a family member. And we are sure there are more. How my father figures into this history of abuse is not something I will ever know. I am sorry if something happened to him, in the way that I am sorry when I hear of any abuse. But it is not a consideration when I face his abuse of me. After all: I am not an abuser. My aunt (whom he also abused) is not an abuser. My mother, abused by her own father, was not an abuser.

It is a myth that victims of abuse go on to abuse. It is a dangerous and wholly inaccurate assumption, one which partly absolves perpetrators of responsibility and accountability. The truth is, abused in childhood or not: the decision to abuse is down to the abuser. It is the abuser’s fault. No one else’s.

All of the abused women in my family have tried, and mostly succeeded, to break the intergenerational line of sexual abuse. My mother’s attempt to save me from her suicidal and infanticidal actions — her more or less throwing me from her sinking boat onto the boat which appeared to be floating, my father’s — was also an attempt no doubt to save me from her abusive past, and the fear of how she might harm me. She said to me many times that giving me up was the hardest thing she had ever done, and that she was wracked with grief for over a decade afterward, until I went to university. Later, when I told her about my father’s abuse of me — all of her sacrifice must have seemed for nothing. Must have destroyed whatever she had left, on all fronts.

Two and a half years after she died, I am finally going through her things. As I’ve known for a while, this is all — somehow — my next book. The photo above is I believe her graduation photo, from high school. She went on to the University of Texas at Austin and did a double major, in English Literature and Maths. She was smart. Very, very smart. The loss of herself over her lifetime is heartbreaking. So much promise, so much life. She was 79 when she died, destitute and completely alone in a high security nursing home, trailing a number of psychiatric diagnoses. In the pandemic. Despite our years of trauma with each other, it was the thought of her dying alone which really undid me, the night I received the email.

This short excerpt from my memoir — now titled Leaving Locust Avenue — recounts when I told my mother about my father abusing me.

***

Back [at university] for my final semester, I now begin to tell everyone else in my life about my father’s abuse of me. My close friends, including Lia and Dan and Alice (two of whom, it turns out, have their own stories of abuse), and, at my therapist’s urging, my mother. The longer I hang onto this, she says, the more damage it does. The longer I protect people, the more I hurt myself.

So. I ring my mother after that Christmas and Winter Term, back in my house at Oberlin. And, after she becomes angry at me for being in therapy ‘again’ and why am I not yet ‘over’ my early life with her, I tell her.

She is speechless. Apoplectic. Understands now why I came to live with her [when I was 17]. Wants to know more details than I can possibly say right now. There is so much I can’t yet say.

And soon after, within a couple of weeks, more secrets. My mother herself starts having flashbacks, and begins to remember being abused by her own father at a very young age. She tries to tell me details, but I cannot listen. I don’t want to listen. She tells me instead some of the things my father did to her – demand that she sleep with him after their divorce, when he was already remarried, nearly rape her when they were married, follow her, spy on her.

This all makes an awful sense, but it’s a weight I cannot carry, and she clearly cannot help me. My mother and I drift apart again. She enters a downward spiral, which leads more than once to hospitalisation and psychosis, and I find that I must stay close to the people I love, and whom I know love me, the people who know right from wrong even when I can’t see it, especially of course R. By the summer after my senior year at Oberlin we are living together, and by August we are engaged, despite my mother’s protest of ‘not needing to get married’, but thankfully with Ommie and Granddaddy’s blessing.