It’s been a week. My head has been down, to the grindstone. I’ve watched the Maxwell trial spin by. Relief has been followed by distress, and the too-familiar feeling of loss of control: a juror was abused. He helped others to understand the elements of abuse. Along the way another juror realised they’d most likely suffered child sexual abuse as well. All is up in the air.

What does this tell us? For those of us in the Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) world, it reinforces a few hard facts, all of which we know, all too intimately:

- CSA is very common. In the UK, the NSPCC can be sure that 1 in 20 children is sexually abused. In the US, the CDC splits this figure by gender: 1 in 4 girls, 1 in 13 boys. These are the surveyed and reported stats.

- There is also the hard fact that a third of those abused NEVER disclose or report it. So we can be sure that the figure is higher than either the NSPCC or CDC can report in good faith.

- No one likes to think that the person next to them has been a victim of child abuse. See number 1. No choice, folks.

- No one likes to think that there’s a chance that the crimes being tried were experienced on some level by a member of the jury. See number 1. No choice, folks.

- Nor that anyone in any context knows or has contact with anyone who was sexually abused as a child. See number 1. You, and everyone, are bound to know numerous people who have been abused. No choice, folks.

Here is the thing. As late as 1974, Child Sexual Abuse was considered extremely rare. 1 in 1 million people. My lord. Society and culture could then (incorrectly) be supported by medics’ and lawyers’ claims that CSA is virtually unknown. From there, silences, denials, dismissiveness, deflections…all of that seemed fair enough. Nothing to do with Us. What happens to those children, and those people, is not Us. What happens is strange. Perverted. Deviant. Not Us.

Yes. I’m not going to argue anything other than CSA is awful. Wrong. Deviant.

But it IS Us. It is an everyday occurrence. It deserves to be part of the conversation, even in trials around…CSA. Because who would think of having no differently abled people on a jury in a trial about discrimination against disabled folks? Who would think about requiring there be no people of colour on a jury in a trial which involved a person of colour?

CSA — for this era, and regrettably — is part of the conversation. Part of our lives. Part of your life. We have a voice. We have logic and reason. We can make a judgement. We can hear things out, and weigh things up. But we won’t disregard our abuse.

Juries represent and reflect the Human Experience. Of course the process and the questionnaire all need examining. But let’s not jump to conclusions and state that people who have been abused cannot be part of a jury which must come to a decision about abuse. It’s not gonna happen. And it’s not right if it does.

We all long for CSA never to happen again. But we are nowhere near that yet. As the Maxwell trial, and so much else, amply prove.

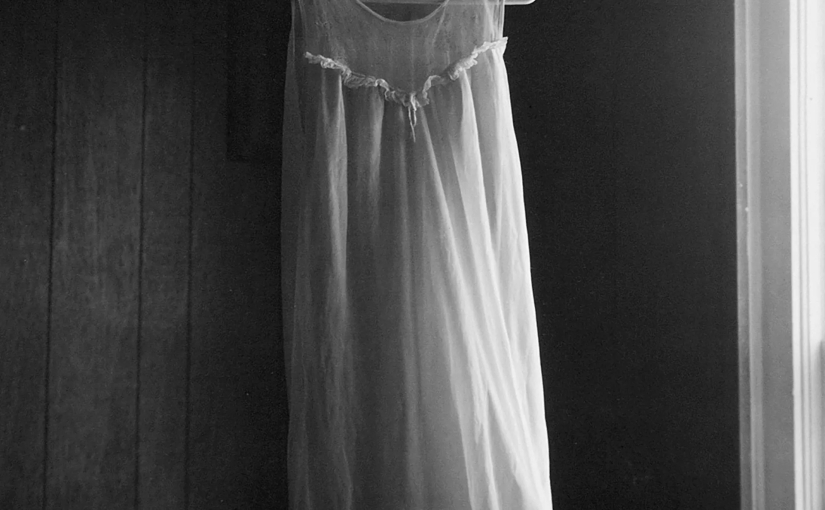

[photo: me at age 15, taken by school friend David Larsen. My father was still abusing me.]

*

from my memoir Learning to Survive, about how very badly we can be betrayed by those who in theory are supposed to protect us, and by an unenforceable law:

Therapy

The spring of my junior year at Blacksburg High School is a particularly gruelling time.

The nerves I see in my father’s eyes become something else, and he appears to take action. He tells me that [my stepmother] ‘knows about us’ and ‘about Suzanne’, giving the impression that he has had to tell her, for my own good. He locates a therapy practice about 15 miles away in Radford which he deems suitable. We are at first booked into a group session; then I start my own sessions, and [my stepmother] and my father start marriage counselling.

This all seems to happen within a couple of weeks. [My stepmother] does not speak to me about what she knows. I do not remember her asking any questions, or expressing any concern. We go back and forth to therapy together, and do not discuss anything said within those walls. From journals of the time, I know that I am deeply, deeply confused and unhappy. About everything. I love Suzanne, but I also like boys. I hate men. I want my father out of my life. And I am utterly miserable.

Things that emerge from therapy:

Every Rorschach ink blot terrifies me. Every single one looks sexual. Looks creepy. Looks scary. Has monsters. I feel I am losing some battle if I admit how terrified they make me feel. I am 17. I lie about all of them, although there is only my therapist and me in the room.

My father requests that I no longer call him ‘Daddy’. You need to grow up, he says, and I need to move on.

Suzanne is a bad influence. I am no longer allowed to see her, at least for a little while.

None of this can be mentioned to [my siblings].

Things that do not happen from therapy:

My father is not reported.

My father is not reported.

My father is not reported.

It takes me a long time to accept – years, and many therapists later – that in this, my first encounter with therapy, I am fundamentally betrayed: my father does not take responsibility for his actions, and, as it turns out, never does, as if that one chance missed lets him off scot-free. As a consequence I am not protected, and nor, for that matter, is [my sister], who is 13 at the time. As a consequence I am completely flattened. If [my stepmother] in theory ‘knows’ now, if the therapists ‘know’, why does everything not fall apart? Is the abuse, after all, okay?

My own unproven and unsubstantiated theory is that my father probably locates this practice precisely because he feels he can influence its members. After all, he has been able to manage every aspect of the story so far. He prevents any explosion, or any impact on any other part of our lives. We carry on. I speak of the abuse – lightly – in therapy, almost paralysed with dread. But it is not discussed much. Of more importance it seems is my relationship with Suzanne: is it real, am I really gay? The therapist seems fixated upon how I become involved with Suzanne, and I do not recall a single direct conversation about the abuse. I wonder if, after all that, she ever really believes me.

I know now that my father almost certainly mis-directed and orchestrated the whole thing, such that [my stepmother] and I never have an honest conversation, and most vitally, [my siblings] are told nothing. I know now too that the therapists at the practice actually break the law: in 1981 in Virginia, therapists are legally obliged to report sexual abuse to the Child Protective Services — which these don’t, because I am never interviewed, and anyway, nothing changes. I know now that this requirement to report to services is in place precisely because perpetrators are generally expert manipulators, and otherwise control the dynamics. Which is precisely what my father does.