I’ve been thinking a lot about my mother over the last few weeks. Her illnesses. Her pathology. Her recurring cries for help.

She unfortunately married an abuser. Who, over ten years after they were divorced, began to abuse me. When I think back to telling her I was abused…I wonder if then, right then, she gave up almost completely.

My aunt and I believe that my grandmother was also abused by a family member. And we are sure there are more. How my father figures into this history of abuse is not something I will ever know. I am sorry if something happened to him, in the way that I am sorry when I hear of any abuse. But it is not a consideration when I face his abuse of me. After all: I am not an abuser. My aunt (whom he also abused) is not an abuser. My mother, abused by her own father, was not an abuser.

It is a myth that victims of abuse go on to abuse. It is a dangerous and wholly inaccurate assumption, one which partly absolves perpetrators of responsibility and accountability. The truth is, abused in childhood or not: the decision to abuse is down to the abuser. It is the abuser’s fault. No one else’s.

All of the abused women in my family have tried, and mostly succeeded, to break the intergenerational line of sexual abuse. My mother’s attempt to save me from her suicidal and infanticidal actions — her more or less throwing me from her sinking boat onto the boat which appeared to be floating, my father’s — was also an attempt no doubt to save me from her abusive past, and the fear of how she might harm me. She said to me many times that giving me up was the hardest thing she had ever done, and that she was wracked with grief for over a decade afterward, until I went to university. Later, when I told her about my father’s abuse of me — all of her sacrifice must have seemed for nothing. Must have destroyed whatever she had left, on all fronts.

Two and a half years after she died, I am finally going through her things. As I’ve known for a while, this is all — somehow — my next book. The photo above is I believe her graduation photo, from high school. She went on to the University of Texas at Austin and did a double major, in English Literature and Maths. She was smart. Very, very smart. The loss of herself over her lifetime is heartbreaking. So much promise, so much life. She was 79 when she died, destitute and completely alone in a high security nursing home, trailing a number of psychiatric diagnoses. In the pandemic. Despite our years of trauma with each other, it was the thought of her dying alone which really undid me, the night I received the email.

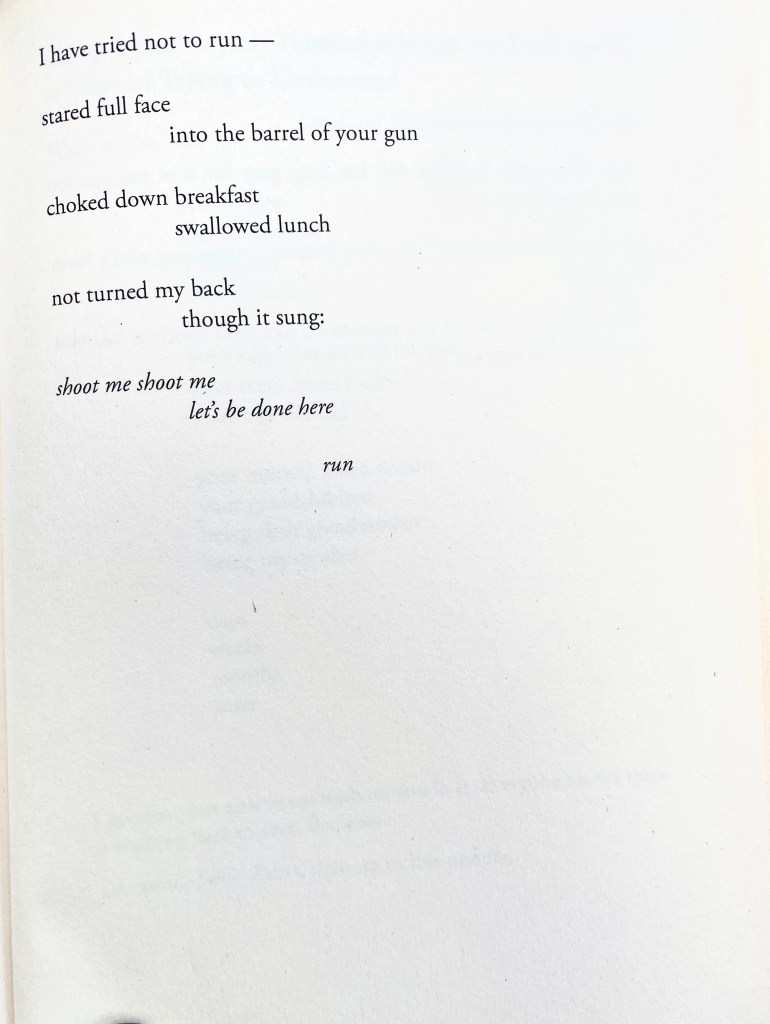

This short excerpt from my memoir — now titled Leaving Locust Avenue — recounts when I told my mother about my father abusing me.

***

Back [at university] for my final semester, I now begin to tell everyone else in my life about my father’s abuse of me. My close friends, including Lia and Dan and Alice (two of whom, it turns out, have their own stories of abuse), and, at my therapist’s urging, my mother. The longer I hang onto this, she says, the more damage it does. The longer I protect people, the more I hurt myself.

So. I ring my mother after that Christmas and Winter Term, back in my house at Oberlin. And, after she becomes angry at me for being in therapy ‘again’ and why am I not yet ‘over’ my early life with her, I tell her.

She is speechless. Apoplectic. Understands now why I came to live with her [when I was 17]. Wants to know more details than I can possibly say right now. There is so much I can’t yet say.

And soon after, within a couple of weeks, more secrets. My mother herself starts having flashbacks, and begins to remember being abused by her own father at a very young age. She tries to tell me details, but I cannot listen. I don’t want to listen. She tells me instead some of the things my father did to her – demand that she sleep with him after their divorce, when he was already remarried, nearly rape her when they were married, follow her, spy on her.

This all makes an awful sense, but it’s a weight I cannot carry, and she clearly cannot help me. My mother and I drift apart again. She enters a downward spiral, which leads more than once to hospitalisation and psychosis, and I find that I must stay close to the people I love, and whom I know love me, the people who know right from wrong even when I can’t see it, especially of course R. By the summer after my senior year at Oberlin we are living together, and by August we are engaged, despite my mother’s protest of ‘not needing to get married’, but thankfully with Ommie and Granddaddy’s blessing.